This book had a huge effect on me as a kid. The idea of being lost, abandoned — it’s a theme that runs through a lot of children’s literature, especially fairy tales, and it reflects a very basic fear. Which of us didn’t get lost as a child? Who hasn’t let go of a parent’s hand in the mall or the park, looked around, seen only strangers’ faces? That feeling of dread and helplessness is familiar to most people.

But Island of the Blue Dolphins takes this primal terror one step farther. Not only is the main character, Karana, lost, she is abandoned by EVERYONE, completely alone on her island except for her brother and the wild dog she tames. As far as she knows, she will be alone forever. And yet…she survives. She figures out how to live. Even when the worst happens, she endures.

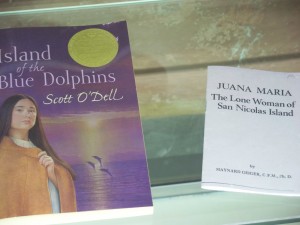

Why am I writing about this? Because I visited the Mission Santa Barbara this week, and found out that the real person on whom Karana is based is buried there. There was a display about her — the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island.

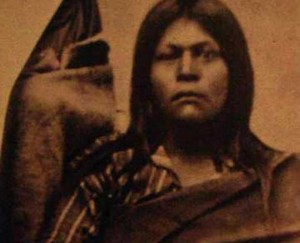

The Lone Woman’s true story, as far as it’s known, differs somewhat from Scott O’Dell’s fictional version. Her people, the Nicoleño, were killed in great numbers in clashes with fur trappers who came to the island in the early 1800s to hunt for otter. The Mission sent out a rescue boat to bring the remaining twenty or so back to the mainland (some versions suggest that the Mission wanted the Nicoleño to work their grounds, as they needed to replace workers who had died). Accounts state that the Lone Woman stayed behind or leaped off the ship because she had been separated from her child, but there’s no proof of this. She may simply have been forgotten. A storm blew up before she could be found and taken onboard, and the ship returned to California. People gradually forgot about her.

Eighteen years passed.

When the Lone Woman was finally found in 1853, she had been living alone on the island in a cave. A trapper who had heard of her story located her and brought her back to the Mission. She was unable to understand or be understood by anyone on the mainland, though she enjoyed the company of people who flocked to see her. She was entranced by horses and clothing, and she ate as much fresh food as she could. But only weeks after her rescue, she contracted dysentery and died. After her death, she was baptized Juana Maria.

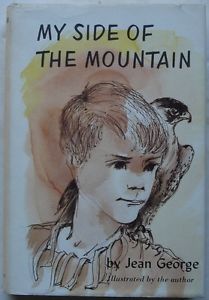

Scott O’Dell’s version is slightly more kid-friendly, making the Lone Woman several years younger than she probably was and giving her a brother and a dog as companions. But the basic story is the same. It enthralled me, the same way other tales of abandonment and survival did — My Side of the Mountain, Hatchet. Or even stories about kids isolated by their differences — Harriet the Spy, From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, A Wrinkle in Time. The idea that a young person can endure and even thrive in isolation helps, I think, to assuage the feeling of aloneness that all children feel at some point in their lives. And few characters in children’s literature are as utterly alone as Karana.

Juana Maria’s life is a testament to what humans can endure. Her story’s real, tragic ending was a blow to me when I read about it at the Mission — I didn’t remember having heard it before. I’m glad I didn’t know it when I was ten. But I’m also glad that Scott O’Dell chose to immortalize the Lone Woman in a novel that kids still adore, even fifty-four years after it was first published.