I love writing children’s books.

I love writing children’s books.

LOVE IT.

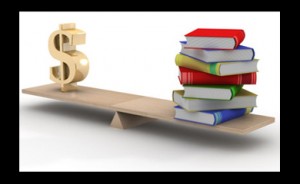

But almost no one who writes children’s books makes a living at it. Unless your initials are JKR, you’re probably going to have to supplement your income. That’s just how it is. I’m incredibly lucky that my “day job” is writing — or at least I considered myself incredibly lucky until pretty recently.

I write textbook lessons, mostly in ELA (English Language Arts) for kindergarten through twelfth grade. When I started out, decades ago, there weren’t a whole lot of us. We were good at what we did. We knew the difference between a gerund and a participle. We knew where commas did and did not belong. We knew that Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” was really not appropriate to quote at a commencement. We could define and identify a theme. We could write, on demand, a 250-word essay on penguins, a one-act play set in outer space, a rhyming poem in iambic tetrameter, and a magazine article about earthquakes, along with the composition lessons teaching those forms — all in the same week. We got our assignments directly from editors at publishing houses, and though our names didn’t appear in the textbooks, we were paid relatively well for work that was, for the most part, enjoyable. And it was IMPORTANT.

knew where commas did and did not belong. We knew that Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” was really not appropriate to quote at a commencement. We could define and identify a theme. We could write, on demand, a 250-word essay on penguins, a one-act play set in outer space, a rhyming poem in iambic tetrameter, and a magazine article about earthquakes, along with the composition lessons teaching those forms — all in the same week. We got our assignments directly from editors at publishing houses, and though our names didn’t appear in the textbooks, we were paid relatively well for work that was, for the most part, enjoyable. And it was IMPORTANT.

We wrote the materials that educators used to teach your children to read and write.

In the late 80s and early 90s, the economy suffered a downturn. Educational publishing companies laid off a lot of editors. Many of those editors opened what they called “development houses” and what we called “packaging companies.” Now the packagers got the assignments from the publishers and called us to do the writing. We did the same work, but our pay was cut because of the packager’s overhead — by a quarter to a half.

Some of these packagers weren’t very good at what they did. Many went bust — often without paying their writers what we were owed. Educational publishing continued to downsize, with mergers of companies adding to the number of out-of-work editors. Many of them became writers, and some of them were not very good at what they did. There were fewer textbooks being published and more writers to do the work. The result was that our pay was cut still more.

Then came the crash of 2008. Publishers lowered the amount they paid packagers, and packagers passed the pay cut on to us. Now we were making about a third of what we had made twenty years before — for the same amount of work. When the economy started to recover, our pay didn’t. Publishers and packagers had realized they could get the work for less, and they had no reason to change. It didn’t seem to matter to them that a lot of the writing they were getting was inferior, because many of the writers who had started out in the business had given up or found other career paths. So now, at a time when the entire industry is undergoing enormous changes with the implementation of the Common Core, many of the people who could best write the materials urgently needed for a new curriculum have disappeared. Those who have stuck with it are faced with the task of writing two or three times as much as they used to, just to pay the bills.

Then came the crash of 2008. Publishers lowered the amount they paid packagers, and packagers passed the pay cut on to us. Now we were making about a third of what we had made twenty years before — for the same amount of work. When the economy started to recover, our pay didn’t. Publishers and packagers had realized they could get the work for less, and they had no reason to change. It didn’t seem to matter to them that a lot of the writing they were getting was inferior, because many of the writers who had started out in the business had given up or found other career paths. So now, at a time when the entire industry is undergoing enormous changes with the implementation of the Common Core, many of the people who could best write the materials urgently needed for a new curriculum have disappeared. Those who have stuck with it are faced with the task of writing two or three times as much as they used to, just to pay the bills.

In the last two years, I’ve been on a number of projects that have all had the same trajectory. I get a call from a packager asking if I’m available. I ask about the project and the pay, get an answer that’s feasible (barely). I sign on.

The project is delayed — sometimes for weeks, sometimes for months. Having signed on, I often turn down other jobs. I scramble for work to fill the gap.

I often turn down other jobs. I scramble for work to fill the gap.

The project starts up. Half the writers have dropped out. They are replaced by second-choice writers. The end date hasn’t changed, so we have to write the same amount but twice as fast.

The project is halted. It must be rethought. A couple of weeks go by. The packager calls — the work has changed radically and now we can only get half the page rate we were originally promised. The end date, of course, is still the same.

When I can, I quit these projects. When I can’t, I have to do my best to deliver as skillful a job as possible, at half the price in half the time. And I do it, because I take pride in my writing. And because textbooks are IMPORTANT.

But the next time you hear horror stories about educational materials that are badly written or full of errors, you don’t have to wonder what happened. The bottom line has replaced any desire for a job well done. The confusion in planning and implementing these projects results in a product that is rushed and poorly developed. Writers are a dime a dozen — almost literally. We aren’t valued, and our work is no longer as valuable. In the scramble to make a buck, educational publishing seems to have forgotten the one thing that really matters:

But the next time you hear horror stories about educational materials that are badly written or full of errors, you don’t have to wonder what happened. The bottom line has replaced any desire for a job well done. The confusion in planning and implementing these projects results in a product that is rushed and poorly developed. Writers are a dime a dozen — almost literally. We aren’t valued, and our work is no longer as valuable. In the scramble to make a buck, educational publishing seems to have forgotten the one thing that really matters:

We write the materials that educators use to teach your children to read and write.